By 3400 BC the Mesopotamians of Sumer had a writing system, and soon afterwards the Egyptians also had one. The use of writing to record all sorts of literature and write personal letters and so forth begins around 2100 BC. The Chinese developed writing by about 1600 BC. People in Central America work out a writing system by about 1000 BC.

The invention of writing.

In the second half of the fourth millennium before the common era (from 3500 BC to 3000 BC) the merchants and scribes of the cities along the lower Euphrates and Tigris rivers used crude pictographic images to make administrative notes or records. Barry Powell suggests that actual writing begins in Mesopotamia around 3400 BC. During the centuries of the first half of the third millennium before the common era, (3000 BC to 2500 BC) the pictographic writing system of Sumer evolved into a more phonetic system, and the people of Sumer began to write down prayers or historical records in addition to their business and temple transactions. In the second half of the third millennium before the common era (2500 BC to 2000 BC) the Sumerians began to write down many of their literary works, such as myths and stories that had been part of their oral tradition, but there was not yet a flourishing of literary work inscribed on clay tablets. The earliest written work of Sumerian literature dates to about 2600-2500 BC, from Abu Salabikh, and it is a wisdom text, the Instructions of Shuruppak. In the first half of the second millennium before the common era (2000 BC to 1500 BC) the Sumerians and others around them began writing everything. We find in the archeological record of clay tablets with cuneiform writing from these centuries all sorts of letters, essays, fables, stories, hymns, legends, myths, and so forth.

The other writing system nearly as old as Sumerian cuneiform is the hieroglyphic writing of Egypt. This appears shortly after Sumerian writing, by a matter of decades, or perhaps a century. The earliest Egyptian writing is primarily dedicated to recording names and events. Like pre-linguistic writing in Sumer, early Egyptian graphic systems conveyed meaning without necessarily conveying specific words. This sort of expression of meaning using graphic systems or memory aids was also used in the pictorial documents of the Nahua tradition in Mexico (around the time the Spanish conquered the Americas), and the cord notation system of the Incas (khipu), which coded meaning and information without necessarily using a word-to-symbol or sound-to-symbol correspondence. Similar sign systems of meaning exist today with corporate logos, common graphic images of men or women to represent gender-specific bathrooms, or the use of numerals, which correspond to different words depending upon the language in which they are embedded, but convey meaning about numbers that transcends specific languages.

One thing these early writing systems had in common was that they were not alphabetic. Mesopotamian cuneiform writing was syllabic and partly ideographic, much as Mayan writing was. Egyptian and Chinese writing are logographic. The invention of alphabetic writing comes with the innovation of West Semitic writing around 1500 BC (it may have begun centuries earlier, but alphabetic writing did not really catch on until around 1300 BC).

Literacy was not widespread in ancient eras when writing was new. Perhaps 1% of Egyptians or Sumerians were literate (but some estimates go as high as 4%). In the first centuries of its use, writing was used mainly as an aid to memory in bureaucratic administration, or in recording commercial transactions. For centuries we have early writing that mainly records commercial transactions, storage inventories, victories of rulers, and that sort of thing. Mayan glyphic writing was later also used primarily for recording historic events and marking time. But, we are also unsure of how much writing was going on. Many cultures wrote on materials that have not survived through history, and the writing on stone in Egypt or inscribed on brass in China is possibly not representative of the typical writing that was prevalent.

An interesting exception to low levels of literacy in ancient civilizations was the case of Deir el-Medina, where skilled craftspersons worked on Egyptian tomb construction in the Valley of the Kings around 1550 BC to 1080 BC. Literacy may have been as high as 40% among the men and women who worked in this village.

The Chinese writing system appears between 1600 and 1200 BC in cast bronzes and carved in bones and turtle plastra (belly pieces). But, it surely was invented long before its appearance, because as soon as it appears it already has three to five thousand logographic signs. Presumably for centuries Chinese had been writing on wood, bamboo, silk, and other perishable surfaces, so that when the writing appears around 1500 BC it had already been significantly worked out and refined. But it does not go back to the neolithic YangShao culture represented in the finds at Banpo. At that time (4800-4000 BC) people were using signs with some sort of meaning, possibly representing personal names like modern corporate logos. For that matter, research on ancient cave art from over 15,000 years ago shows that there was a finite number of signs used across much of the world, and those signs may have been universally understood as representing specific abstract concepts, but they were not really written language.

Written language was invented at least twice, once in Mesopotamia in about 3,400 BC, and again later, around 1000 BC in Central America. The Chinese may have invented it independently, but they probably got the idea from their trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia, where writing was used for about over 1500 years before it shows up in China. The written language of the civilizations of the Indus River Valley dating back to nearly 2000 BC are also probably inspired by the Mesopotamian writing systems, as the people of the Tigris-Euphrates rivers were in regular trading contact with the people of the Indus River.

-

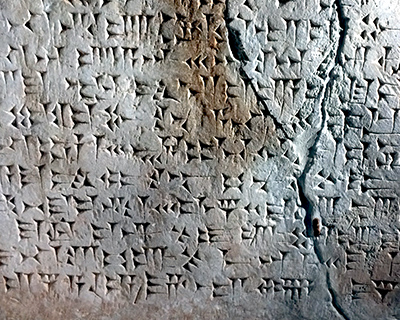

An example of cuneiform writing carved into stone. This inscription praises King Sargon, and dates to sometime between 2330-2290 BC.

-

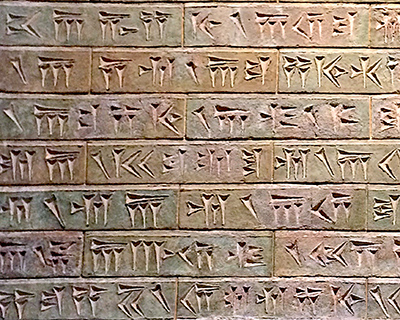

These glazed bricks use cuneiform writing in Old Persian language to ask a blessing for King Xerxes (486-465 BC), who ruled over 1,800 years after King Sargon.

-

This memorial stone celebrates the life of Nefershe, who lived around 2250-2200 BC.

-

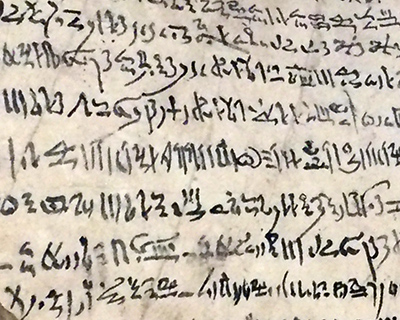

This is an example of the hieratic script used in most Egyptian writing; it is a sort of cursive version of hieroglyphic writing. This particular sample is from 1185-1170 BC.

-

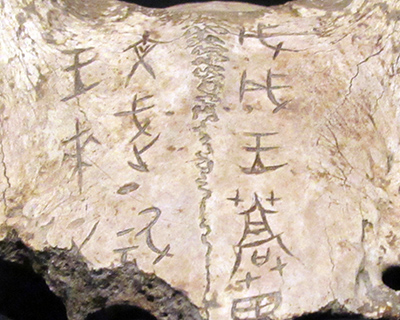

One of only two oracle writing samples found on a deer skull, dated to about 1200 BC.

-

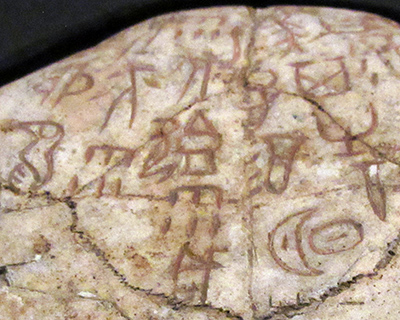

The more typical type of oracle script is found on turtle plastra like this one. In the lower right corner the moon and sun symbols together had a meaning related to "tomorrow" or "the future" just as the Chinese character 明 today, which is still made of symbols for a moon and sun, concerns the future when combined with a character for a unit of time (combined with the character for "day" it means "tomorrow," and combined with the character for "year" it means "next year").

-

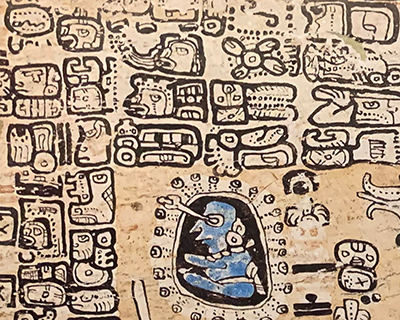

This is an example of a writing system of the Americas; it is a copy of the Codex Tro-Cortesianus, which is one of the four ancient Mayan manuscripts that have survived down to the present day. The Mayan writing system seems to have evolved from earlier writing systems used by the Olmecs and Zapotecs perhaps a thousand years before the Mayan civilization arose. Mayan writing usually constructs words with symbols that correspond to syllables in the spoken language.

Links about Writing:

- Joshua Mark summarizes information about the history of writing at the Ancient History Encyclopedia website.

- Bridget Alex at Discover Magazine has an article in 2019 What the Earliest Texts Say About the Invention of Writing.

- This cartoon Youtube video does a good job of describing the invention of writing.

- Jeremy Norman’s History of Information The Instructions of Shuruppak, Some of the Earliest Sumerian Literature.

- Irving Finkel is an engaging speaker, and an expert on cuneiform writing, and here is one of his lectures about cuneiform.

- Barry B. Powell (2009) Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization.

- Ben Haring (2018) From Single Sign to Pseudo-Script.

- Georges Jean (1987) Writing: The story of Alphabets and Scripts.