Between 3300 and 3100 BC the early agricultural civilizations along the Tigris and Euphrates, and also along the Nile, developed governments, large towns that could be considered cities, and complex divisions of labor and bureaucratic hierarchies. By 3100 BC Egypt all along the Nile, from the lower delta area in the north to the upper areas far to the south had been unified under a Pharaonic system. Centuries later, around 2334 BC, Sargon, the ruler of the Mesopotamian city state of Akkad expanded his political influence through most of Mesopotamia. The only other contemporary civilizations that were urbanized and probably had codes of law at this time would be the Caral Civilization (or Norte Chico Culture) of what is now the central Peruvian coast and the civilization rising along the Indus River in south Asia.

While it seems likely that both the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations regularly established legal codes and had them written and distributed, historians give much attention to one of the earliest codes of law to survive down to the present in written form, the code of Hammurabi, which dates to 1792 BC, a little over 500 years after Sargon established his empire, and approximately 1,300 years after the unification of Egypt under a Pharaoh.

Hammurabi’s laws were not the first. Some rules and laws dating to the rule of Uruinimgina in Lagash around 2374 BC have survived, as have about half of the law codes of Ur-Nammu who ruled over Ur, Eridu, Uruk, and Nippur. Ur-Nammu’s legal codes date to around 2100 BC or 2040 BC (chronologies are not certain). So Uruinimgina’s laws predate Hammurabi’s codes by over 550 years, and Ur Nammu’s codes are 250-300 years earlier than Hammurabi’s.

Mesopotamia had several different ethnic groups. Five of the significant ones were:

- Sumerians (who spoke Sumerian, a language without known links to any other language),

- Akkadians (who spoke an eastern Semitic language),

- Amorites (from northwestern highlands, and speaking a western Semitic language),

- Elamites (from highlands to the east of Mesopotamia, who had the city of Susa, who practiced equality of men and women, and spoke a language with no known relationships to other languages), and

- Gutians, also from areas to the north and west of the city states along the Tigris and Euphrates, and also speaking a language isolate.

King Hammurabi was an Amorite, and he lived during the period from 2000-1600 B.C. when the Amorites were most influential and dominant in Mesopotamia. King Hammurabi had his armies defeated and destroyed the nations of Mari and Ur, and the destruction of Ur ended independent Sumerian Civilization, which merged with the Amorite kingdom of Babylon ruled by Hammurabi. The settled Amorites such as Hammurabi who lived in Babylon had adopted many of the religious and cultural aspects of Sumerian civilization, so the end of independent Sumerian city states as they were unified in the Akkadian empire of Sargon, and then later the First Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi, was not really an end of Sumerian culture.

King Hammurabi was the most successful king of the First Babylonian Empire, ruling from 1792 to 1750 BC. There was a second Babylonian Empire that rose to dominance about 1100 years after the days of King Hammurabi and the first Babylonian Empire. It is that second Babylonian empire that figures prominently in the Bible. Also, the best evidence suggests that the Ur mentioned as the home town of Abraham in the Bible was located in what is now Southeast Turkey, and is now called “Sanliurfa” or “Urfa”, and was not the city state of Ur in Mesopotamia.

The First Babylonian Empire wasn’t an impressive empire until Hammurabi had his military successes, which took him many years to accomplish; as he did not complete his conquest of neighboring states until about 1762 BC. Before Hammurabi, there were five previous kings in Babylon, and after Hammurabi, his successors presided over 155 years of decline and loss of territory until finally in 1595 BC, Babylon was sacked by the Hittites ruled by Mursilis I, and the Hittites handed over Babylon to their allies the Kassites.

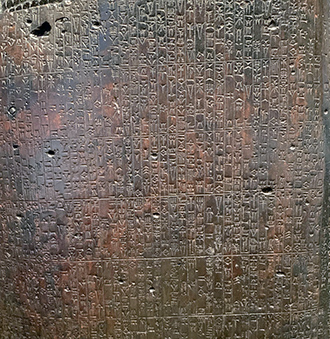

After conquering most of Mesopotamia, Hammurabi proclaimed his legal code. There are a total of 282 legal articles in the code. The full text of the code was carved in cuneiform on a black basalt stone 2.25 meters high, which is now in the Louvre museum in Paris. Elamites from Susa brought the stele with Hammurabi’s laws as war treasure when they defeated the Kassites around 1160 BC. Although some of the laws were erased from the famous stele in the Louvre (probably by the Elamites), many other copies of Hammurabi’s legal code have been found, and the laws seem to have endured in successive empires for hundreds of years with little change. The legal code was engraved in Akkadian, which was the language of Sargon and the Akkadian Empire (2334 to 2154 BC).

There are many court cases and judgements that can be found on cuneiform clay tablets from the First Babylonian Empire after Hammurabi, and from these it appears that the laws of Hammurabi were not applied in actual court decisions. They probably served a purpose of showing general principles of assigning punishments to persons whose guilt was established. The laws of Hammurabi have a prologue and epilogue, which emphasize that the purpose of the laws is to protect the weak from the aggression of the strong. The codes also specify three class levels in society: a gentry or aristocracy, a level of commoner, and an underclass of slaves. If a noble person kills another noble, the penalty is death, but if a noble kills a slave, the noble may offer a blood price to compensate the owner.

Hammurabi’s code endured with few modifications for many centuries in Mesopotamia. Like many laws, it offers legitimacy and a conservative preservation of privilege and exploitation in society, but at the same time it attempts to offer commoners and slaves some degree of justice and protection from unfair treatment or exploitation. Thus, it exemplifies the tension in governments, of trying to create stability and protect the interests of those with power and wealth, while at the same time putting constraints on the powers of the gentry and providing for some protections for those who are poor or enslaved. Like many legal codes, including those in the Bible, the laws of Hammurabi claim to be inspired by Divine sources, and not merely the artifacts of human imagination and invention. The famous stele in the Louvre shows at the top an image of Hammurabi receiving the laws from the sun and justice god Shamash, sitting on a throne and handing to Hammurabi a scepter of earthly power.

-

The Code of Hammurabi was carved in cuneiform on stone.

-

The stele of "The Code of Hammurabi" shown in the photo is a replica, displayed at the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.